Cable House with trench dug for cable still visible. Telegrapher George Green is just visible under the trees in the front of the house. He marked his upper bedroom window with a black dot.

Carolyn Ravenscroft

Many of you are no doubt are familiar with the Landing of the French Atlantic Cable in Duxbury in 1869, but for those of you who have never heard the tale, gather ‘round…

Once upon a time, before smart phones and email, before telecommunications, before even Marconi’s wireless, there was only one way to communicate immediately to those far, far away – cable telegraph lines. You may not be surprised to learn that Samuel Morse, of “Morse Code” fame developed and patented the first electric telegraph machine in the US in 1837. But, interestingly, the code for transmitting messages could just have easily been called the “Vail Code” since Morse’s assistant, Alfred Vail, was responsible for it, but such is life when you’re not the boss. By 1861 almost every point in the United States, from California to New York, was connected via wire. So long Pony Express, hello telegram.

As amazing as connecting the vast North American continent by wire was, there was still a more daunting feat to be accomplished, a transatlantic cable. With a Victorian can-do attitude and an initial $1.5 million in capital, businessman Cyrus F. Field, along a group of backers, set out to make the world a bit smaller. It took five attempts and over ten years before the ship, Great Eastern (read more about the ship), successfully laid a 2,000 mile-long cable across the ocean floor from Ireland, bringing it ashore in Newfoundland in 1866.

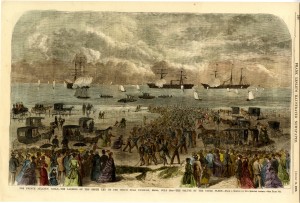

Once Great Britain and North America were connected, the French sought to have their own exclusive means of transatlantic communication. As with the Anglo line, the French Atlantic Telegraphic Company used the now tried and true Great Eastern. The French cable was approximately 3,500 miles long – beginning in Brest, France it would travel to the “southern edge of the ‘Grand Banks’; thence to the French island of St. Pierre off the south coast of Newfoundland and thence down past Cape Breton Island and Nova Scotia to Duxbury.”[1] On June 21, 1869 the Great Eastern, accompanied by the ships Chiltern and Scanderia set out on their voyage. Just over a month later, on July 23, 1869 the cable was landed on Duxbury Beach at Rouse’s Hummock.

It was a time of great celebration in Duxbury. A tent was erected on Abrams Hill with a view of the Hummock. Six hundred guests, including dignitaries from around the state, nation and world converged to wine, dine, listen to speeches and most importantly, to see first hand the wonder of sending and receiving messages from across the sea. Included in the festivities were Mayor N. B. Shurtleff of Boston and President of the Massachusetts Sentate, George O. Brastow.[2] Cannons of the Second Massachusetts Light Battery were fired, streamers and flags flew and for a moment the eyes of the world were on this sleepy seaside town.

The eventual terminus for the cable was the former Duxbury Bank building on the corner of Washington and St. George Streets. As you can imagine, the early years of the cable office were quite busy and required trained operators, many of whom, like Englishmen Robert Needham and George Green, immigrated to Duxbury along with the cable. Later, Canadian William Facey, the amateur photographer responsible for one of our most-used photo collections, came to work here. These men became some of Duxbury’s most civic-minded residents. After a few years the French Atlantic Cable Company was brought under the fold of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company and later, in 1911, became Western Union. Over the years other transatlantic cables took away Duxbury’s prominence and business waned. Duxbury’s cable house closed after WWII.

Today the stately home on the Blue Fish River that once housed the cable office is a private residence. It is still alternately called the “Bank Building” or the “Cable Office” by folks in town…okay, that’s probably not true, it’s called that by a handful of people, including me, but nobody knows what I’m talking about when I say it. Now you do.

If you would like to learn more about the French Atlantic Cable, you can visit the Drew Archives and view the Robert Needham Collection (DAL.MSS.043), the French Atlantic Cable Collection (DAL.MSS.044), read telegrapher George Green’s own copy of Landing of French Atlantic Cable with his notes, or see the images in the William Facey Collection online at http://www.flickr.com/photos/drewarchives/sets/72157626060922690/

[1] Franklin K. Hoyt, The French Atlantic Cable 1869, Duxbury Rural & Historical Society, 1982. p. 8

[2] The Landing of the French Atlantic Cable, Boston, Alfred Mudge & Son, 1869.