The following is a memoir written by Duxbury native, Pauline Winsor Wilkinson (1836-1924). Pauline was the daughter of Capt. Gershom and Jane Winsor and was born on Powder Point Ave. When she was four years old her father was lost at sea off of Cape Hatteras, leaving her mother with five children to raise alone. In 1859 Pauline married Isaac Otis Wilkinson, a Boston merchant and friend of her brother’s. Although they resided on Rutland Street in Boston’s South End, Pauline was a frequent visitor to her hometown. The Wilkinsons, with their three children, moved to Berkley, California in 1876. Sadly, Isaac died the following year. By 1890 Pauline had returned east and was residing in Brookline. In her final years she lived in the household of her son, Crayton, again in California.

Pauline Winsor Wilkinson wrote her memoir in 1921, when she was 85 years old. It is a wonderful picture of Duxbury during its shipbuilding days.

OLD DUXBURY

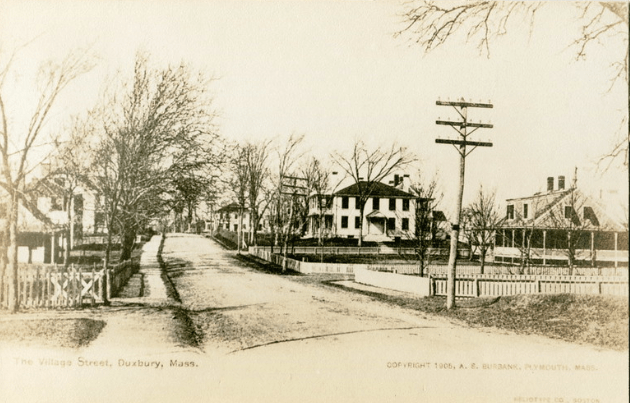

In looking back at Duxbury eighty years ago [1840s] one sees a great change. In those days the town was occupied only by the natives and life there was simple and plain. Once in a while it would be startled by some scandal or a runaway match, but on the whole it was very respectable and remarkably free from squalid poverty or disreputable places. It was long before the era of good roads and they were so sandy that as the heavy four-horse yellow stagecoach made its daily trips to Boston the sand came up on the wheels and fell over on the other side, and it took all day to make the trip. I remember of making it once with my mother to visit my grandmother, who lived in West Cedar Street, Boston.

We stopped at the Halfway House for dinner and a short rest and to change horse, then journeyed on again. the coach was run by “Sprague & Jones” alternately, both of whom lived on Harrison Street in the house still owned by some of Mr. Jones’ family.

There was a wooden bridge over the Blue Fish River, and we who lived on the Point listened to hear the four horses come clattering over it in the evening.

Mr. Jones was not only stage driver, but he did errands as well, as there was no express. I remember going to his house with a sample of green silk from which a dress was being made and asking him to get eight yards of guimp for it about so wide, and the next night when he returned he brought an exact match. He said he could remember about forty errands without a memorandum, but beyond that he had to write them down.

Later the railroad from Boston to Plymouth was built, with a station at Kingston, and the old stagecoach ceased its daily trips to Boston, but it made a morning and afternoon connection with the train at Kingston.

The big stagecoach was later superseded by a “schooner” as it was called, a long black three-seated carriage with two horses – less cumbersome and less expensive to run, no doubt, but far less stately and picturesque.

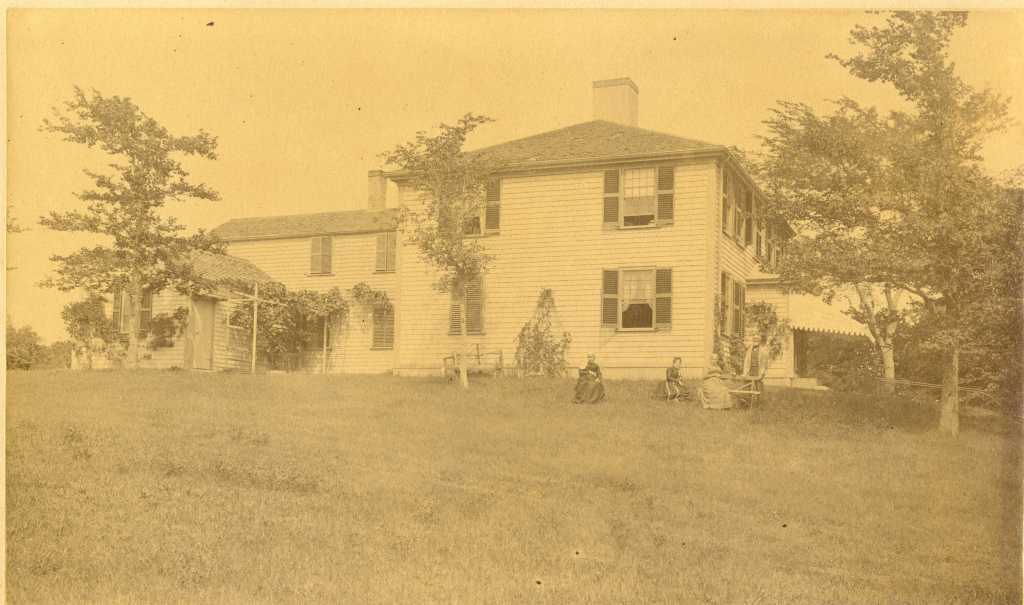

The Point, below Blue Fish River, and the village, were almost like two separate towns, and we of the Point considered that the “court end.” In the eighteenth-century Mr. Ezra Weston was the richest man in town and very autocratic, so acquired the name of King Caesar. It is a tradition that he spelled coffee “kauphy.” He owned all the land on Powder Point and built and occupied a large cottage-shaped house, said to have a secret passage and stairway – but I will not vouch for the truth of that.

It was his son Ezra, I think, who built and occupied the fine large house in which the original landscape wall – paper on the parlor is still preserved [King Caesar House Museum, 120 King Caesar Rd]. He had a large family but after the death of his son Alden in the house stood empty for several years.

In 1886 Mr. Frederick Knapp bought the place and established a boy’s school [Powder Point School for Boys], for which he built a large building, also used in summer as a hotel, and called the Powder point Hotel. It was after he owned the place that King Caesar’s old cottage was burned and an imitation of it built on the same spot.

The Westons built and owned a large fleet of ships and fishing schooners, and Weston’s wharf was a busy place. They also had a store next to the Cushman place [St. George Street]. The house which is now the Public Library was then on the opposite side of the street next the store, and occupied by some of the Weston family.

Gershom Weston, son of Ezra, had a large place and house now known as the Wright place, and kept many different carriages and a colored driver, but the high “buggy” which he drove himself seemed to be constantly on the road. He was a leader in the Temperance cause and had a speaker’s stand in the woods near Round Pond and frequent meetings. He had a yacht, the only one at that time, though the bay was dotted with small sail boats. There was no bridge to the beach, and most of the boats were kept at the Old Cove, and put up for the winter in the boat houses which are now used for bath houses. In those days there were no girl swimmers, they only waded in, but the boys disrobed and plunged in for a swim to “Harrifoot.” There were salt works on the low hill above the Cove and a large windmill, much like the pictures of the Dutch windmills. Mr. Nickerson operated it, and lived in the house now occupied by Mr. Ray Swift’s family [42 Cove St]. One of his daughters, Miss Harriet Nickerson, kept a private school in a small school house that stood on a sandbank on Cove Street between the houses of Mr. William and Mr. Henry Paulding [48 and 66 Cove St.], both of whom worked in Drew’s shipyard (afterwards Paulding’s) which was between the Drews’ houses, where the Steel cottage now stands [no longer standing]. Drew’s wharf opposite was also a busy place. Every house had blinds and after the early morning they were all closed to keep out the flies and mosquitoes which were so plenty that every inch of paint had to be scrubbed with soap and water. We had long poles with a pad on the end with which, while one held the lamp high, we killed all the mosquitoes we could see on the ceiling and walls before going to bed, and then they sang round our ears just as we were going off to sleep, or came in the wee sma’ hours when we were sleeping out soundest, and we found ourselves covered with mosquito bites in the morning. There was no plumbing. A wooden spout led from the kitchen sink to an open drain outside, and we had a big hogshead at one corner of the house to catch the rain-water, so it was no wonder we had mosquitoes and many cases of typhus fever. The fall house cleaning was a terrible ordeal. Every piece of furniture was moved out of each room in turn, the carpet taken up and put on the line a beaten, then turned about, the worn places put out of sight and the best part put where the most wear came. There were no carpet sweepers, and vacuum cleaners undreamed of. Carpets were swept with brooms which raised clouds of dust. How the men dreaded and hated house cleaning time! They had to eat off the kitchen table, couldn’t find their clothes, and sometimes had to sleep in another room.

The seven houses facing the water were occupied by (1st) Mrs. Sampson [6 Powder Point Ave], who had a son Henry and a lame daughter, Nancy Cooper, who walked with a crutch; (2nd) Mr. William Ellison and Mr. John Hicks who kept the Westons’ store [10 Powder Point Ave]; (3rd) the small cottage, by Mr. Cushman [14 Powder Point Ave], (4th) by Mr. Nathaniel Weston, grand-father of Dr. Emerson, the present owner [22 Powder Point Ave]; (5th) Mr. Reuben Drew and his son Capt. William Drew’s family, since known as Mrs. Taylor’s boarding house [30 Powder Point Ave]; (6th) Mr. Reuben Drew also built the next house in 1806 [36 Powder Point Ave]. Then came the shipyard and beyond that Mr. Charles Drew’s house, since known as Captain Adams’ place [52 Powder Point Ave]. I was born and as a child lived in the second Drew house next the shipyard, which was lively then. My mother was allowed to take all the chips she wanted for kindling and once or twice a week we children went out with a big basket to get them. Those big oak chips freshly cut, I can smell them now!

The men who worked there were very orderly, self-respecting townsmen – Petersons, Holmes, Cushmans, Soules, Pauldings. We never heard any loud or foul language and they worked early and late. The large logs for the ships were brought to the shipyard in ox teams – sometimes two and even three yoke of oxen, and our firewood was always drawn by oxen. There were two or three men in town whose only business it was to saw wood. Every house had its woodshed in which the winter supply was neatly piled, oak and pine.

We loved the sound of the axes and hammers, and watched the progress of the vessel building until launching day came when the school was dismissed and people from all around came to see her glide down the ways into the water, the boys on deck cheering and yelling. As soon as she was finished and off another keel was laid. The boys almost lived in and on the water and very many became so fond of its they shipped on the vessels, and in time rose to take charge and in time rose to take charge, and so the town was full of sea captains who sailed the Seven Seas, often taking their wives with them, so they were quite a travelled set, and more intelligent and interesting than the inhabitants of most small inland towns. Each captain had a painting of his favorite ship, and they all brought home pieces of furniture, rich goods, ornaments, curios, etc., making their houses attractive; and most of their families lived in Duxbury the year round, so it was not the deserted looking place in winter that it is now. There were lights in the houses until the modest hour of nine thirty or ten o’clock, but no lights on the streets, and when there was no moon we always carried a lantern if we ventured forth in the evening. Nearly all of them kept a “girl” for general housework at $1.50 a week, but the ladies made their own pies and cake, preserves and pickles. Wages rose slowly and when they got to $3.00 a week, many of them gave them up, considering that altogether too much. Quilting parties were may. The little girls all sewed patchwork and when there were enough “squares” to cover a bed and “tuck in” they were sewed together, then six or eight ladies were invited to the “quilting”, after which a bountiful supper was served.

When the sea captains were at home they drove about town with a gay horse and bright new chaise from the livery stable of the Tavern in the village, kept by one of the Winsors – now the O’Brien House [corner of Washington and Winsor, no longer standing], I think. A chaise was a one-seated covered vehicle with only two wheels and rocked as we rode. Some of the boys who had gone into business in Boston and came down occasionally for a dance or a two -weeks vacation dubbed the Tavern with the name of “The Cracker,” because at every meal they had on the table the large soft crackers that were always used in clam or fish chowder. Clams were plenty then and used only by townspeople who lived largely on clam, fresh and salted fish, lobster, ells, eggs and home-made pork or corned beef in winter. The clam chowder of those days! The clams were large and white rich in flavor, and we often made our dinner on it, with a piece of mince pie afterwards. Almost everybody had a pork barrel in the cellar, a barrel of potatoes, one or more barrels of apples, which we ate freely, and heaps of winter vegetables, cabbages, onions, beets, etc. We always had a barrel of flour, a big bucket of sugar, rye and corn meal, a big demijohn of molasses and one of vinegar, spices, etc., so storm as hard as it might, we had plenty to eat in the house. Then one of the upper windows and a friend, Mrs. Ichabod Sampson, and her daughter Lizzie came prepared to spend the night with us, bringing a pie of loaf of cake with the, and around a bright coal fire and lamp we passed a long and merry evening waiting for the storm to abate before going to bed. If it lasted a day or two they stayed until it was over. those Duxbury days of my girlhood are pleasant to look back upon.

There was a shipyard nearly opposite the Drews’, on the left of the bridge going up the hill, which belonged to Levi Sampson who lived in the large house on the hill, known later as the Hollis House [615 Washington Street]. The post office was next that kept for years by old Mr. Faunce, who lived nearly opposite. His son, Zenas Faunce, had a large blacksmith’s shop at the bridge where now his daughters have a house on the same spot.

In the house directly opposite the Post Office Mr. Joshua Hathaway lived [598 Washington] and had a paint shop near it; next that Mr. Swift’s harness shop, where he made or repaired harnesses and carriages. It had a large raised platform back of it where the carriages were rolled in and out. There was no such thing as a drugstore or Apothecary’s, as they were then called, but each Doctor kept his medicines in his office and carried some about with hi.

There were two doctors in town; Dr. Porter, who had a large practice, going far and near, his old horse jogging on often while the doctor took a nap. He made long calls, often staying for dinner or supper where he happened to be. His wife, too, was very prominent, being very kind to the sick or poor. They had a family of one daughter, Jane, later Mrs. Bancroft, and six sons who all went to California and settled there [The Porters’ house is the site of the Percy Walker Pool].

Dr. Wilde lived in the house now owned by Mrs. Sidney Peterson [45 Cedar St], formerly belonging to Captain Jonathan Smith, whose daughter the doctor married. Some of their grandchildren are still living in town, I believe.

There was a gristmill next the blacksmith shop, run by Mr. Ichabod Alden, who once let some of us children go and put our hands in the warm yellow meal as it fell into the hopper, but we were a little afraid of him so ghostly in his white frock covered with meal dust, as were his hair, whiskers and eyebrows. Later there was a gristmill on the opposite side of the bridge, over which there was some wrangling, and I think it was moved to Millbrook and has long since fallen to decay.

There were four churches. The present Unitarian Church, which replaced the old one with square pews and turn-up seats, which were slammed down when the congregation sat down after the long prayer. People carried footstoves or hot bricks, as there was no other means of heating.

The old Methodist church (now the Episcopal Church) in which there came to be great disagreement, and Squire Sprague and some others seceded. Mr. Sprague nailed up his pew and gave money towards building a new church, called then the Wesleyan Church, now the Congregational or Pilgrim Church.

The Universalist Church, which stood a little further along on Washington Street, but was taken down, and Captain Daniel Winsor bought the land and took it into his place, then very nicely kept, but now for many unoccupied and neglected.

The Point schoolhouse stood next the “spar soak” which the Rural Society bought later and cleaned out the decayed logs and refuse, and placed old Dick’s monument there, which formerly stood on the Weston land and was erected to perpetuate the memory of a favorite horse.

How little the Westons thought that their land would ever be covered with modern houses and become like a suburban town – a Newton-by-the-sea, as some one aptly called it. The newcomers who ha built up the Point with their pretty homes and destroyed the old-time grassy hill where we used to go for a walk to gaze out on both ocean and bay, think they have discovered Duxbury and the beauty of its quiet little bay with the ebb and flow of its water. But they know nothing of the fishing schooners that went out regularly and brought us fish, and the packet that plied between Duxbury and Boston, bringing lumber and supplies for the stores, which kept drygoods and groceries, whale oil, which we burned in our lamps, hogsheads of molasses, and lozenges and stick-candy. This building which you use for the Historical Society was one of them, and here men used to congregate in the evenings around the stove and spin sea yarns, or discuss news of the outer world, which drifted into town slowly, as few took a daily paper. There was Ford’s store in Millbrook, John Alden’s on the left as you turn into Tremont from Alden Street, Sam Stickney’s ice cream shop, where Sweetser’s now is, the same store in the village, and one, I think, at Hall’s Corner. But for little daintier laces or ribbons, when we were getting ready for the Thanksgiving Ball where we wore short sleeves with lace sewed on our short gloves and a bow of bright ribbon, we walked across the pastures to Miss Matilda Peterson’s. she had one front room in her house on Surplus Street, used as a shop, which was very quaint, but not more so than herself, a spinster tall and thin, with her reddish hair in puffs at the sides and a cap with ribbons perched on top of her head, no teeth, her dress scant and old-style even for those days.

There was a school called the Union School which I attended at one time, that was later made into a chapel for the new Episcopal Society which Miss Lucy Sampson was instrumental in establishing in Duxbury. The village Schoolhouse stood, I think, where the present one is, also the one at Millbrook.

It was early in the forties, I think, that Miss Rice came and opened a private school under the auspices of Miss Mercy Frazar in the upper part of the house since known as Mrs. Hammond’s, later on the Fortescue’s a pair of stairs going up on the outside [56 St. George St]. That house and the one opposite were built by Mr. Samuel Frazar who had a shipyard and launched vessels into the millpond [47 St. George St]. Later his son, Amherst Frazar, owned them and his mother and youngest daughter, Mrs. Evans, lived there until the mother’s death. She lived to be over ninety. Later the house was known as the Howard’s who took boarders may summers.

Miss Rice was about twenty years of age, a graduate from a West End public school in Boston, bright and tactful. She made companions of her scholars and soon won their love and devotion, for she brought to them an entirely new element. She developed their imaginations with wonderful stories, some of which she made up as she went along; some were classical myths, which were new to them. She had a class in astronomy and took them out in the evening to study the stars, boys ad girls together – a very popular class. Mr. Livermore was the pastor of the Universalist Church at that time (the last, I think) to whom she became engaged, and left her school and Duxbury, and soon became Mrs. Mary A. Livermore and a very prominent woman, contemporary and friend of Mrs. Julia Ward Howe, Miss Abbey May, also Mrs. Judith W. Smith, all of whom were leaders for then unpopular movement for woman suffrage. Mrs. Smith, now ninety-seven years old, is the only one who has lived to see its final adoption by the nation. Mrs. Livermore wrote a very pleasant account of Duxbury and its people in her autobiography.

After Miss Rice left, Mr. Stephen N. Gifford opened a private school in Masonic Hall. He had a knack of imparting knowledge and inspiring his pupils with a desire to learn, and kept good books on his table which we might borrow when we had good lessons and retire into the woodroom to read. For several winters where were Lyceum lectures in the basement of the Wesleyan Church, for which he got many of the lecturers, Anson Burlingame, a Mr. Otis, and Judge Russell among them, all young and cultivated men, the Judge an intimate friend of his. He was afterwards sent to the Legislature, then was clerk of the Senate, which office he held for nearly thirty years. He was instrumental in getting the railroad from Boston via Cohasset to Duxbury, and interested also in getting the monument to Myles Standish on “Captain’s Hill,” as it was always called. Years before he took his scholars down there and pointed out the cellar of Standish’s house that was burned, and taught us to reverence the Pilgrims.

Always when we went to Plymouth, which was seldom, as it took nearly all day, we went into Pilgrim Hall religiously and pored over the relics of the Mayflower people, their guns and armour, spectacles, pocket books, and crude house keeping implements, or some little personal belonging of one of the women, with a kind of awe. I have always wondered that as a people we gave so little thought to that small brave band, who for conscience’ sake came to this desolate shore in the dead of winter where there were only savages, who might be cannibals for all they knew, and planted a new nation which has grown to be the richest and most powerful because it was planted by Godfearing people of sterling worth and honestly. May our leaders come to a realizing sense of that and, as this is their tercentenary year, perhaps they may be reminded of them and their high purpose, and strive to emulate their good example.

It was about that time, I think, that Mr. George Partridge left money to the town for an Academy, and in 1844 the Partridge Academy was opened and Mr. James Richie was the first teacher, and a good one, much respected and loved by his pupils a few of whom he fitted for Harvard College, they being apparently more ambitious than Duxbury boys of the present day. For three years through rain and shine, slush and snow and ice, my sister and I walked the long distance, unless picked up by some kind neighbor. We carried our luncheon in a tin pail, and no mince pie nowadays, though much richer, ever tastes like the big pieces of cold mince pie that came out of that pail, with raised cake full of raisins.

Later Mr. Gifford bought what was Mr. Henry Thomas’ [4 Cedar Street] that family having moved to Boston after their little son Wentworth was drowned in the millpond. Mr. Thomas had for years the care of the Daniel Webster place in Marshfield, which he bought from Mr. Thomas’ father. As a young girl I remember of standing on the wall of Dr. Wild’s place and see the procession go by escorting Mr. Webster from the station in Kingston to his home in Marshfield. It was after one of his great speeches in Congress and the people turned out to do him honor. He rode in a barouche and without his hat, bowing his acknowledgements to their cheering and waving of flags, his large dark eyes, swarthy skin and weary look still lined in my memory. Not very long afterwards, in 1852, we attended his funeral at his home. People came from far and near in every kind of conveyance. It was a warm October day and the casket was placed under the big elm three near the house, where he used to sit so much when at home. The railroad station not far from his place was called Webster Station. His family has died out, the property fell into other hands, the name of the station was changed to Green Harbor, so all trace of the great man has gone from this vicinity.

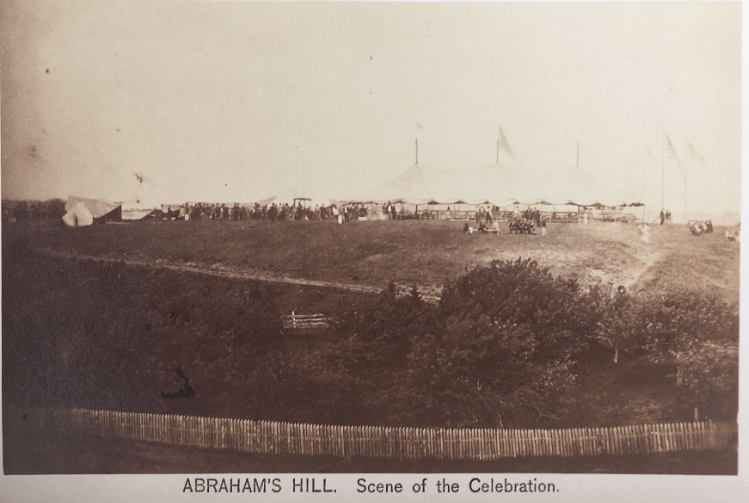

When the French cable landed on Duxbury beach there was a great celebration and we thought it would build up the town, but except for a few new families it went on about the same. Some of the young men connected with it coming from France and England married Duxbury girls and settled down in the town, becoming as much a part of it as the natives.

It was a custom in the summertime for the women to lie down after the midday dinner and have a nap. Every blind was closed in every house and the town looked deserted. The about four thirty or five o’clock the parlor blinds were thrown open and the town was awake and ready for visitors, as “calling” was very much in vogue.

It was on such a day that my fate rode into town. It was a hot July day and we lay stretched out on the bed, the music of the hammers in the shipyard lulling us quickly to sleep, when suddenly we were wakened by the sharp summons of “get up and dress quickly, for Fred Sampson has brought his friend, Mr. Wilkinson to see you.” “Oh, can’t you excuse us?” “No, they didn’t come to see me, and you girls must come down just as quickly as you can” and she was gone. We never thought of disobeying our mother, so we arose at once and much against our wishes went down when I met my fate – fortunately a happy one.

Bath rooms were unknown. Every house had its pump in the kitchen sink, or out of doors, and all the water had to be carried up stairs and down. Sewing machines had not been invented and there were no ready-made garments even in the city stores. Little girls were all taught to sew, and women were kept busy with socks and the children’s scarves and hoods, and had little time for gadding about. But I think there was much more family life than at the present time, more cozy evenings around the evening lamp and reading aloud, though there were no town libraries then. Sometimes we played old Maids, Everlasting, or Dr. Busby, checkers of backgammon. Later Euchre came in.

Then, as now, we had a Fair in August in the Academy Hall, which was planned and captained principally by Mrs. Daniel Winsor, who set us all at work, whether we would or no, and the result did her and all the ladies credit. One was for an organ for the Unitarian Church when they made $1000. And the very handsome and substantial cemetery fence was paid for in that way, the whole town being interested and working for that.

The dear old cemetery! So quiet and retired from the gaiety and bustle of the summer life; where so many of our dear ones lie, as they drop away one by one. And many who left the town even twenty-five or thirty years ago come back to lie in that quiet peaceful place, where only the wind among the pines and the song of birds break the stillness. It is a hallowed spot that we old timers all love.

In my girlhood days the Unitarian Church was well filled in the summer. In July and August the well-to-do people had relatives and friends come from Boston and other places to visit them for a few weeks, and then the town was wide awake and lively, boating, riding, picnicking and tea parties. As a grand wind-up of the season there was a Parish party to which young and old went and danced the round dances, cotillion, Hull’s Victory, Virginia Reel; such pretty, friendly parties; white-haired men and ladies in caps, young married people, engaged couples, and young men from Boston and other places who had heard of or met some of the Duxbury girls. That was on Friday night and Saturday was the big picnic to Brant Rock. There was but one house there then, an old-fashioned farm house not far from the rock. All sorts of vehicles were put in commission and young people and old went to that. We had clam and fish chowder, fried fish right out of the water, lobster, huckleberry pies and cake, and many other good things but we noticed the chowder was served in large white bowls very like the wash bowls upstairs! On Sunday the big church was full. After the service the vestibule was like a reception, people greeting and parting, as most of them left the next day, though a few stayed on to enjoy the warm, hazy days of early fall.

There were many peculiar people in town, real characters, about whom one might have written tales equal to some of Miss Wilkins’, funny but pathetic stories of country people. There was Mary Ann Alden, a direct descendant from John and Priscilla, who sat in a north ‘wing pew’ at church and during the long sermon of Mr. Moore, watched out for all the young people and visitors in town and made her peculiar and cutting remarks about them afterwards.

Lois Brewster, in one of the southing pews, made her observations also, and at one time when there were three new engagements in our set, hurried down the church steps and tapped me on the shoulder, saying “I like the looks of your young man best of them all.”

Bidley Soule a giant of a man in size, slouching and dirty, but with keen wit, who put the puzzling epitaph on his mother’s gravestone “The chisel can’t help her.”

In the winter we retuned the visits our relatives and friends and got our taste of life in the city and suburbs, our first acquaintance with theaters, opera, concerts, etc.

Once on coming home in the Spring we left Boston on the 6thor 8thof April just as it was beginning to snow. When we got to Kingston, only the mail carriage with one horse was there to meet the train as the storm was so bad. With some difficulty we got as far as Hall’s Corner, when the driver said he could take us no further as the drifts were so deep between there and the village, so we had to spend the night at Mr. Charles Soule’s at the corner.

The Point boys skated on a pond at the Eagle Tree, since called Wright’s pond. If any girls attempted it with their brothers’ skates they were called tom-boys. But they slid on the ice and went coasting on sleds. The sleighs went juggling about, and once in the winter, usually, a big sleigh-ride was gotten up to go to Cohasset or Hingham and have a supper. They went in a big boat – shaped sleigh that held about twenty people. They chose a moonlight night, danced after supper, and came home long after midnight, waking up people along the road with their singing and the jingling of the sleigh bells. There were no houses on what is now the Standish Shore, the last house being Mr. Marshall Soule’s later known as Mrs. Lyman Drew’s [152 Marshall St]. She took summer boarders and first attracted people to that part of town. Mr. Drew at one time had a dancing school in Masonic Hall. He played violin well and always played at the dances.

Mr. John Wilde had a singing school in Duxbury for years and in those days the young people of a neighborhood in the summer evenings collected on the doorsteps – there were no piazzas – and sang together the popular songs, all joining in heartily, being not so critical as now, though one or two were the acknowledged leaders.

As each set of young people grew up the summers were kept lively and enough people lived here the whole year to make some sociability in the winter time. It was in the seventies that the ladies of the Unitarian Society bought a building Brooks stable and express office, fitted the lower part for their sewing room with kitchen, etc., and made a hall with a fine floor for dancing upstairs. It was called Duxborough Hall.

They had a janitor and on Saturday nights gave ten cent parties which were very popular, informal and lively. For some time it was the only hall. The ladies enjoyed their meetings with a luncheon and did good work. But gradually they died or moved away until so few were left the meetings were given up. A larger hall, Mattakeesett, was built for dancing or movies on the lower floor. Finally Miss Hathaway generously bought Duxbury Hall and presented it to the Unitarian Society for their Parish House and in the winter months they hold services there.

What is now Mrs. Horace Soule’s house formerly stood down nearly on the shore, occupied by a Peterson family, and was called Hautboy Castle, though what gave it that name I don’t recall. Mr. Nathaniel Thayer of Boston, who came with his family one summer to board at the Howard’s discovered the sightliness of its present situation and had it moved there, remodeled, (piazzas, etc.) in the seventies and occupied it several summers. Then Mr. Train came with his family of lively young people, when tennis was introduced and raged here. The place is still in the Train family, being owned by the youngest daughter.

Duxbury is changed, perhaps, for the better. Now it has its yacht club, its tennis courts, and its golf links, its tea houses and gift-shops. The roads are good and automobiles fly hither and thither constantly. More and more the old houses are being bought and remodeled and new ones built with electric lights and every convenience.

The ship-builders and sea captains, the Westons, Frazars, Drews, Sampsons, Winsors, Soules, Winslows, Freemans, Thomases, have passed on. The town is full of new names. Monied men have come here and bought up land and houses, rents are raised so that people of moderate means, who remember the old time charm of its pure air and warm sea bathing, its restful quiet and informality, find it hard to get a place. Circumstances have taken me far from it. To revisit it now I should feel like Mr. John Porter who went away when he was a lad of nineteen and came back after twenty-five or thirty years of life in California. When someone asked him if he found many of his old friends and acquaintances he replied, with tears in his eyes, “I find most of them in the church yard.” Yes, the old town has changed, probably improved – but in recollection and association it will always be the dearest spot on earth to me. If the time ever comes when the earth sidewalks with grassy edges are replaced by asphalt with stone copings, I am thankful I shall not see it. It is the Old Duxbury I remember and love.

Berkley, California April 1921 Pauline Winsor Wilkinson

Pingback: 52 Ancestors, Week 18: Social – Our Prairie Nest