By Carolyn Ravenscroft

This article originally appeared in the Lamplighter, Spring 2022

When Duxbury’s iconic Nathaniel Ford and Sons store opened on Tremont Street in 1826, it was only one of many neighborhood “general” stores catering to a local clientele. Although the Ford Store would go on to be hailed as the country’s first department store, selling a wide variety of goods in its ramshackle and rambling buildings, it was never the only place to shop in town. The Ford family’s fame overshadows the dozens of other Duxbury proprietors who served the community throughout the nineteenth century.

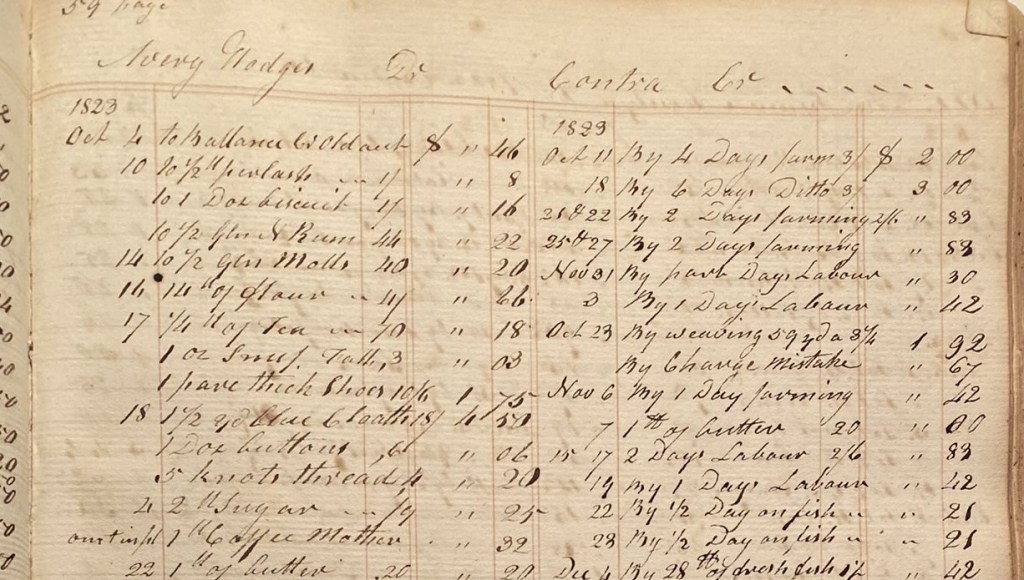

Before the advent of the automobile, Duxbury was a town of villages where most daily tasks were accomplished within the confines of your neighborhood. Whether you lived in the charmingly named Tarkiln, Ashdod, Crooked Lane, or Tinkertown; the eponymously named Fordville, Chandlerville, or Gardnerville; or the practically named South Duxbury, you likely had a school, shops, and craftsmen within walking distance. That was very important when you made frequent forays on foot. When it came to shopping local in 1826, the year the Fords hung out their sign, there were at least five other general stores on the east side of Duxbury, each selling similar wares to their local patrons. Judah Alden’s store was on the corner of Tremont and Alden Streets, creating the hazardous bend in the road that we still live with today. Ezra Weston, aka King Caesar, had a store on St. George Street, directly across from the Wright Building. The Drews’ kept a store on Powder Point, William and Henry Sampson operated a shop at 318 Washington Street, and Sylvanus Sampson’s store was on Standish Street. There were, I am sure, instances when our 19th-century counterparts chose to trek longer distances to get better eggs, cheaper spices, or a more stylish bonnet, but for the most part, basic necessities could be had close to your front door.

Some items did require specialty shops or planned excursions. Fine thread for crewelwork and lovely embroidered ribbons were sold out of the front parlor of Matilda Peterson’s house on Surplus Street, for example. A trip to her shop was a treat fondly remembered by many of Duxbury’s young women. When even Matilda’s offerings did not suit, there was always Boston or Plymouth. The latest books, French wallpapers, fine silks, fancy carpets, etc. could all be had in the city’s many mercantile establishments. The daily packet boat could sail you to Boston and ship your purchases home to Duxbury. The stage coach could also take you, or you could place an order with the stage driver who would pick up what you needed. After 1845, you could also catch the train to the city from Kingston.

While many of the goods sold in 19th-century stores were locally sourced or imported from Europe and Asia, some of the staples were the products of Southern and Caribbean slavery. The Ford’s first sale included four gallons of molasses, fourteen pounds of sugar, one gallon of New England rum, and 1/4 pound of tobacco. The molasses, sugar, and tobacco were all directly produced by enslaved people. The New England rum was distilled also using sugar from the West Indies. While cotton cloth or thread was not part of this first sale, it was likely sold later in the day. This complicity between the Northern and Southern economies did not go unnoticed. When the anti-slavery movement grew in the North, forgoing such items was one way to show support for the cause. But, even staunch abolitionists like the Bradford family of our Bradford House Museum continued to purchase sugar, cotton, and molasses in the years preceding the Civil War, demonstrating how pervasive and necessary these products were.

Throughout the 1800s, stores would come and go, thrive and fail. Some owners would pack up and head west, hoping for better luck in a new boom town; some would change occupations altogether. Federal-era homes would become storefronts only to be converted back to residences by the next owner. The history of retail is an important part of Duxbury’s story and is often as interesting as that of our great shipbuilding wharves.