By Carolyn Ravenscroft

This article first appeared in the Lamplighter, Fall 2023

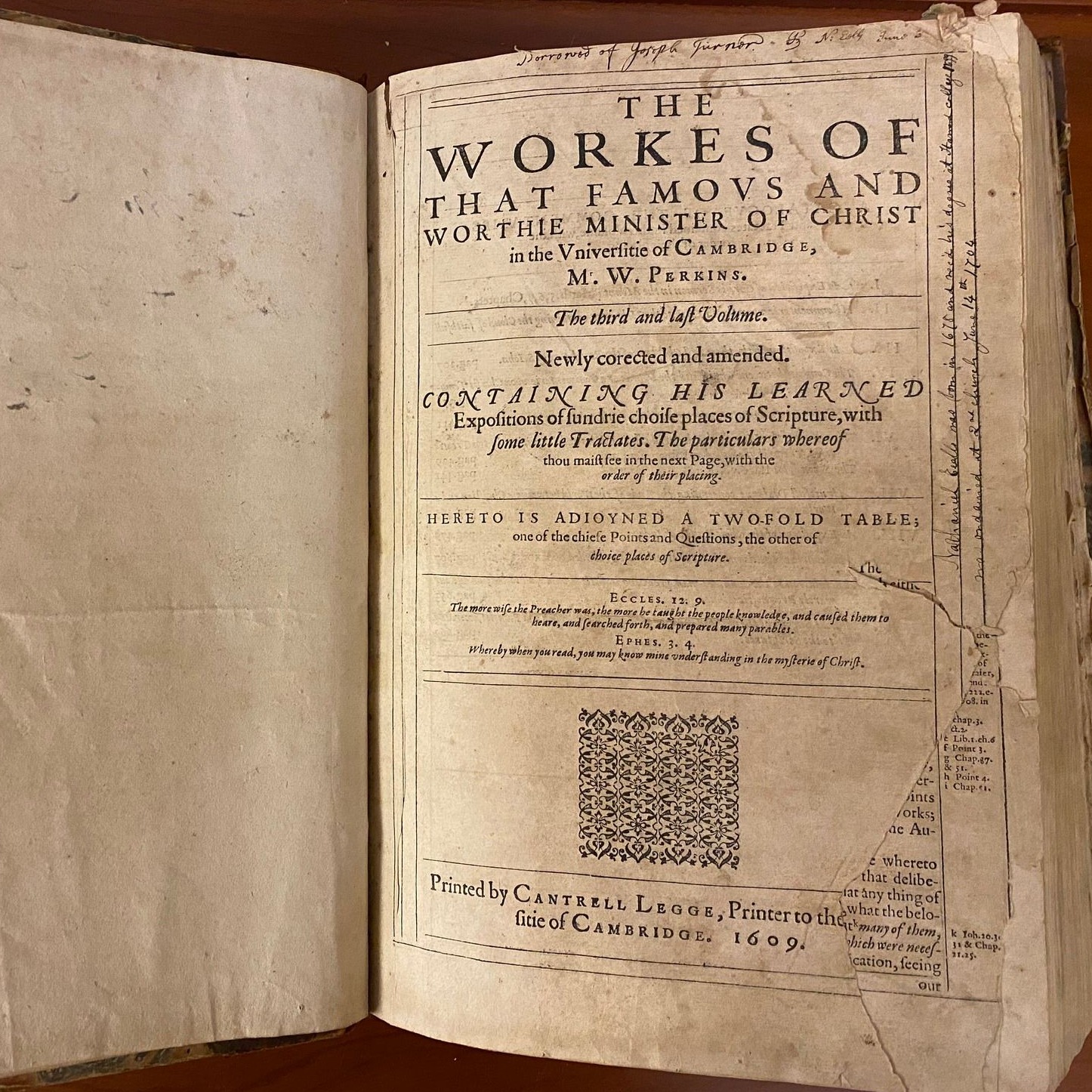

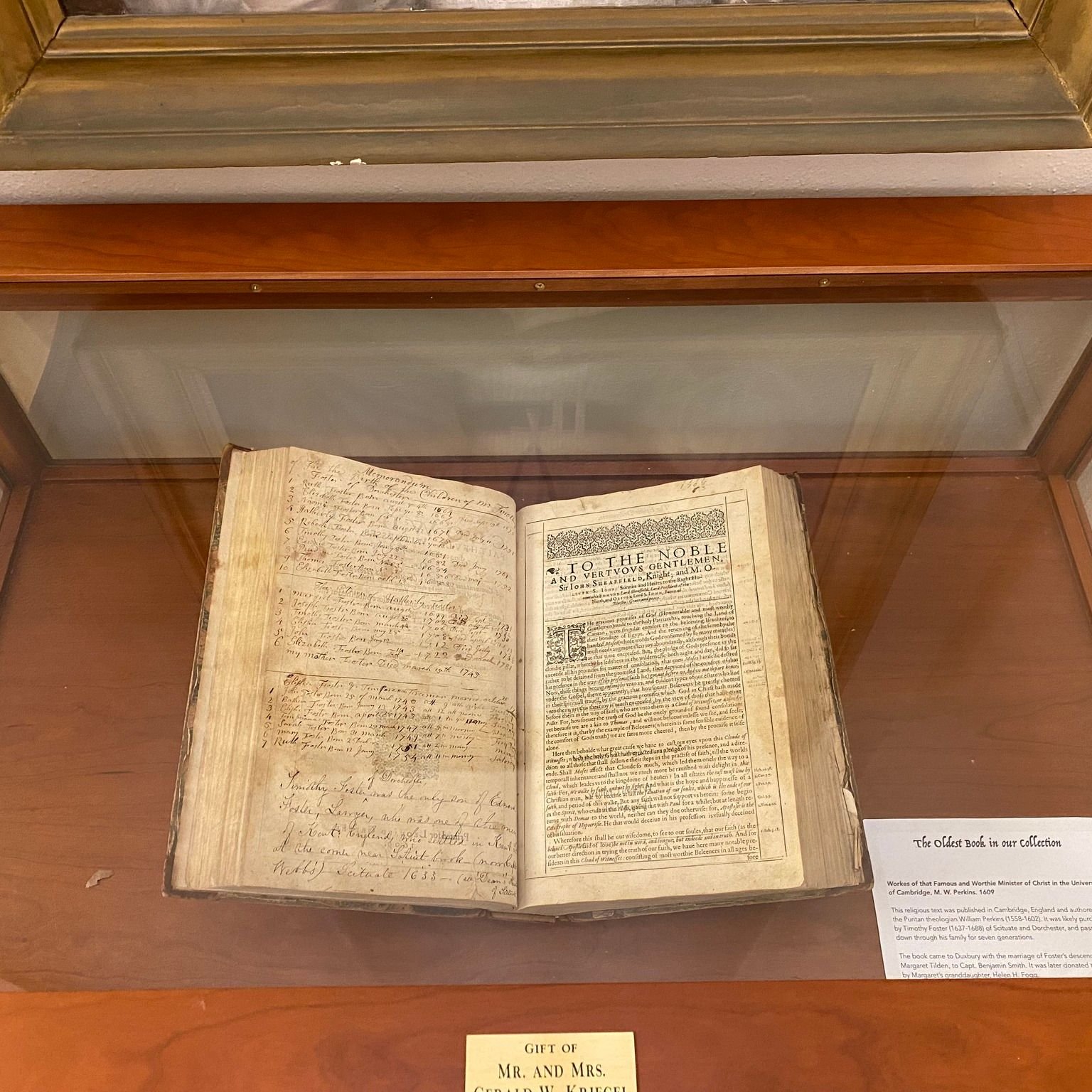

October is the perfect time to describe the oldest, and maybe spookiest, book in the DRHS’ Drew Archival Library’s vast collection. The Workes of that Famous and Worthie Minister of Christ in Universitie of Cambridge, M. W. Perkins. Published in England in 1609, the book is a compilation of the writings of the noted Protestant Reformation theologian Rev. William Perkins. The volume is large, measuring 12″ x 8.5″ x 2.5″, and is bound in leather with marbled end-papers. This is not, however, the original binding. The pages were cut down at some point, as evidenced by partially missing handwritten notes on the top margins of some pages.

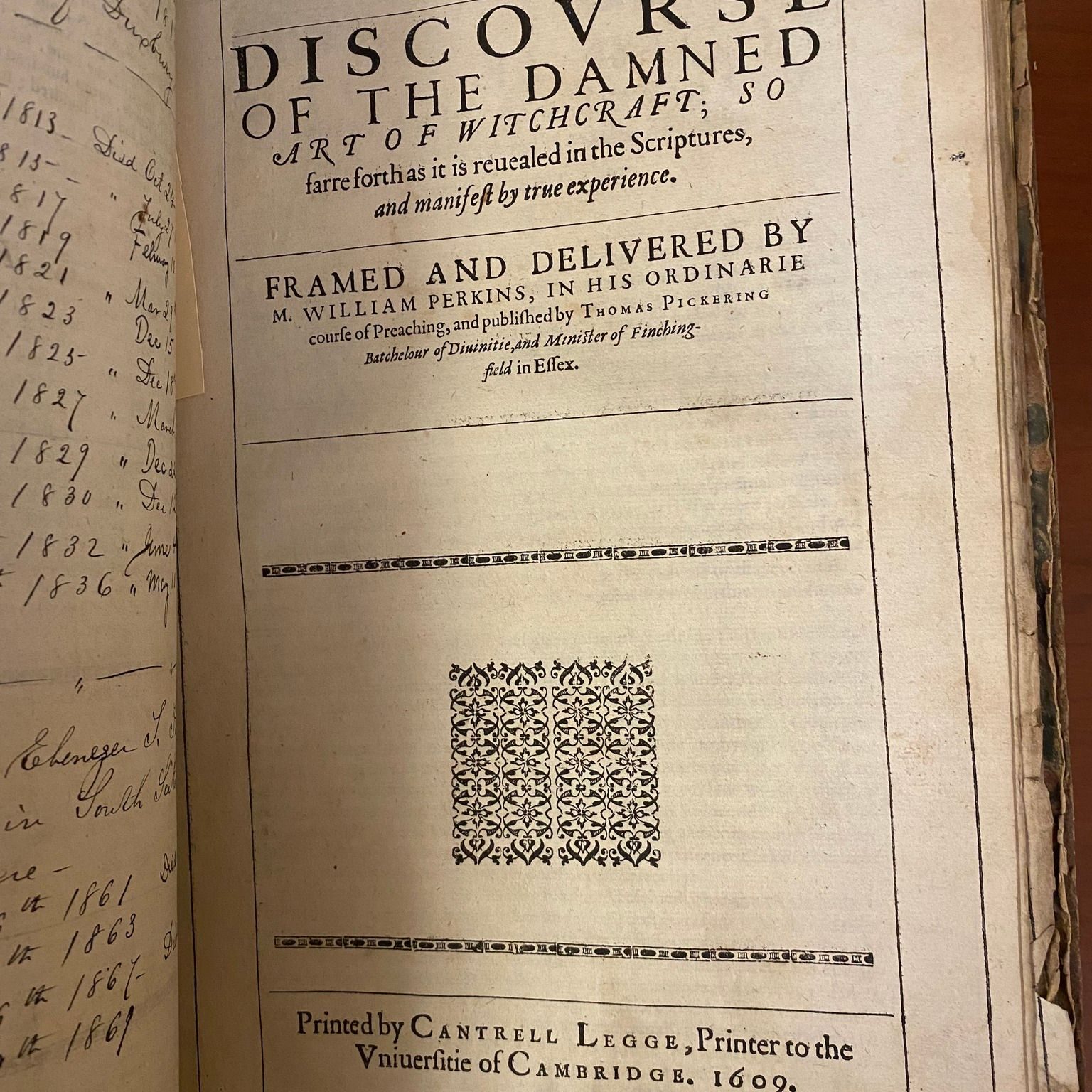

The book’s almost 700 pages contain eleven commentaries on religious subjects by Perkins. Today’s reader would undoubtedly find the commentary A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft the most intriguing. Witches were not the stuff of fairy tales or legends in the 17th century; they were very real beings. According to Perkins, the practice of witchcraft was “rife and common in these our dais, and very many are intangled with it.” Perkins described witches as those who made a pact with the Devil. They could see into the future, use the black arts, and make wonders occur through charms and spells.

While the section on witches and how to expose them is fascinating, it is the book’s ownership and the hands through which it has passed over the centuries that interest me the most. A number of handwritten notes scattered through the pages tell the history of this book. Beginning with the very first page, we have the large, scrawled signature of “Benj’n Smith Jr. Duxbury.” This is followed on the next page with an almost equally large signature of Smith’s sister, Helen L. Fogg, with the note “from H. E. Smith, Feb’y 9th ’88.” With these two pages, we can place the book in Duxbury by the 1800s. Capt. Benjamin Smith Jr. (1814-1848) lived on Depot Street and is buried in the tomb on the corner of Tremont and Depot Streets. Hambelton E. Smith (1817-1892) was the Captain’s brother, who lived at 1043 Tremont Street when he gave the book to Helen L. (Smith) Fogg (1832-1909). It returned to Norwell with the Fogg family until the book was donated to the DRHS by Helen’s daughter.

Despite Benjamin Smith’s oversized flourish, the book did not originate with a Smith ancestor in the 1600s. It was gifted and loaned many times, and that is part of the fun, to piece out who owned it, where, and when. While we may never know who brought it to the New England colonies, our story begins with Deacon Joseph Turner (1649-1724) of Scituate, the son of one of the town’s founders. Turner wrote on a blank page about 3/4 of the way through the book, “Joseph Turner his book God give him grace to in it to look.” Perhaps he studied its pages upon hearing of the witchcraft trials in Salem in 1692. He loaned the book for a time to Rev. Nathaniel Ells Jr. (1677-1750). In 1698, Turner’s daughter Bathsheba married Deacon Hatherly Foster in Scituate. The book eventually made its way to Bathsheba’s son, Elisha Foster, who recorded three generations of Foster births within its pages, beginning with the children of his grandfather, Thomas Foster of Dorchester. This “Fosterization” of the book makes it appear that it had been in the hands of the Fosters since the 1600s, but these early births were written by Elisha in the 1750s. A later page includes the birth of Peggy Foster on August 5, 1772 at eight in the morning. Peggy would go on to marry Samuel Tilden. Their daughter Margaret Tilden (1791-1851) of Scituate married Capt. Benjamin Smith Sr. of Duxbury in 1812. The Smith’s children included the above mentioned Benjamin, Hambelton, and Helen. So, it is easy to trace more than 300 years of the book’s history from Scituate to Duxbury.

You can see the book by appointment at the Drew Archival Library.