Carolyn Ravenscroft, Archivist

The Drew Archives is very fortunate to house the large Bradford Family Collection – a collection that, I may have mentioned once or twice before, contains thousands of items and spans over two hundred years. A goodly portion of this collection relates to the Civil War – a number of the family fought or were involved in some way, including, of course, the army nurse and diarist, Charlotte Bradford. The collection also contains letters from another key Civil War figure – Frederick Newman Knapp, the Special Relief administrator for the USSC in Washington, DC. Knapp was not only Charlotte’s boss while she was a Transport Ship nurse and the matron of the Sanitary Commission’s Home for Soldiers, he was also her niece’s husband. We are lucky to have his papers here, especially those that directly relate to his work in the USSC.

The following is a letter by Knapp in Frederick City, MD to his parents in Walpole, NH, written almost two weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg. Knapp was in charge of seeing supplies made their way to the battlefield and ensuring that the army had what it need to care for the wounded. It is remarkable in its detail as Knapp recounts the confusion in orchestrating such a large-scale relief effort. For any scholar of the Sanitary Commission, this letter sheds light on a little discussed aspect of the USSC’s overall operations and certainly brings to life one of its most faithful servants. As the transcriber of this letter, however, I have to say that Knapp’s writing is challenging. He has perhaps the worst penmanship of any of the 19th century figures in the Drew Archives. He was an educator for most of his life but obviously was not concerned with having a “good hand.” If you would like to know more about his life, a recent article in Historical Digressions gives a nice overview.

Frederick City, July 16, 1863

Portion of letter written by Knapp to his parents on Sanitary Commission letterhead. Annotations in pen were made by Knapp’s nephew, Gershom Bradford.

Dear Father and Mother,

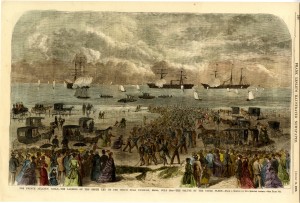

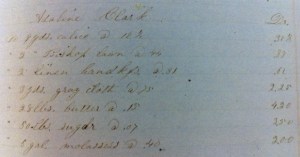

All well. This has been a busy week with me or a busy ten days. Nothing like it since the York River work when we had to fit out Hospital Transports at a days notice. The work has been to get supplies of all sorts with least possible delay to Gettysburg, all then to Frederick: at Gettysburg to meet terrible needs: at Frederick to be prepared for what might be even greater needs in case of a battle which might come off at any moment at Hagerstown or in the region of which Frederick would be the safe base of supply. In getting stores and Relief Agents to Gettysburg we had to meet the difficulty of getting a blocked Rail Road – single track with cars by hundreds loaded with wounded in the one direction and supplies for 20,000 men in the other – so that we not merely had to meet immediate needs but keep a supply, if possible, of two days ahead. The result has been most gratifying & successful, and repaid all labor two hundred fold. “Special Orders” & special messengers and teams by turnpike – and supercargoes and constant personal presence at points of shipping goods have secured results which I felt at first could not be made. Not a train left Baltimore for Gettysburg for some days that did not take from 25 to 300 cars of our supplies – estimate only by tons – a number of entire carloads direct from Philadelphia or Boston transferred from Phila Road to the Northern Central Road (thence by branch road to Gettysburg) but most of the supplies carted from across Baltimore to Central R.R. Depot – 100 or 200 tons at a time. Then beside the general supplies there were the answering the requirements of Special demands by telegram & letter from Dr. Douglas at Gettysburg – such as “send me 1000 loaves of bread – 40 barrels fresh crackers – ten relief agents, six carpenters, six cooks – 100 yds oil silk –and entire outfit for first class Relief Station – including tents, stoves, supplies, etc. – all by first train up from Baltimore if possible.” We have every day for a week sent to Gettysburg (and one time 2 loads daily) an “arctic car” load of fresh supplies ½ ton each of poultry, mutton, butter, fresh vegetables, etc, etc. Some days two (2) car loads – until at last a telegram from Gettysburg cried “hold, enough” (except the arctic supplies). Meantime horses and wagons & saddle horses & harnesses, etc. etc. had to be selected & bought & drivers & wagon-masters selected and bought and started off (in last week I bought & fitted out the nine wagons & 18 wagon horses & five saddle horses). Then came the necessity to send goods to Frederick in anticipation of a great battle in this region – Mr. Olmsted went to Frederick and immediately telegraphed “push on supplies with all possible dispatch by every means in your possession.” So new telegrams to Philadelphia & N. York & Boston had to be sent telling what we wanted via one car load a day for each place besides express loads. These supplies arriving had to be carted over to the Frederick Station, loaded – disentangled from [?] stores and got through – all the material for first class Relief Station including tents, etc. etc. cooks & men got & sent – with wagons & horses, etc. Meantime bills had to be paid and all the agents at work kept straight…Since Monday week we have received there at Baltimore between 80 & 90 telegrams all to be attended to and I have made purchases of horses, wagons & supplies in sums from one dollar to 500 amounting in total to $18,000 – and kept it all straight. So you can see why I haven’t written you any long letters – and though it has involved so much work I can assure you I have enjoyed it greatly and was never better in my life…Josiah Bellows is recovering at the cars which bring the wounded from Gettysburg to Baltimore – a wagon & two [unreadable] & 3 or 4 others in each train to give the water & care for them. We also take all these cars at Baltimore and purge them & put fresh straw, etc. & water & ice & crackers, etc. This we do by special request of Major [unreadable] staff in charge of transporting the wounded. I bought fifty water coolers (for ice) in one day for the cars.

Must close – I have gone over this to show you the Comm are at work – the Relief they have given at Gettysburg is immense…

Your affectionate son, F.N. Knapp