Carolyn Ravenscroft, Archivist

In 1856 seventeen-year-old Ardelia E.Ripley (1839-1899), the daughter of Samuel E. Ripley and Sarah Cushman[1], was a student at Partridge Academy in Duxbury. Her Common School Book-Keeping Being a Practical System by Single Entry; Designed for the use of Public Schools by Charles Northend (1853) can be found at the Drew Archives. It is a wonderful example of how students learned the art of basic accounting. While we have numerous day-books and journals used by adults of the period, it is unusual to see one that demonstrates the learning process. Practice books are often thrown away long before they make it into an archival collection.

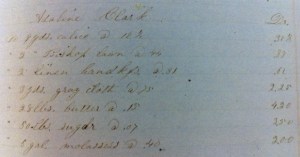

What I find fascinating about the book is what it tells us about society in the 1850’s. Here, in neat script, is a full listing of all the items a person might consider purchasing along with their cost. Duxbury was no longer the prosperous shipbuilding mecca it had once been, but that did not mean its inhabitants didn’t still pine for kid gloves and cashmere. Using her classmates and relations as fictitious “customers” Ardelia itemized a veritable Ante-bellum wish-list. Classmate Frederick Bryant, for example, lavishly spent $6.00 on “1 pair of pantaloons for my hired man” but also more sensibly required coarse salt at 1 ¾ per pound, and even a “white wash brush” for $.63. Girlfriends like Josephine Thomas bought “muslin de laine ($.31 per yard), 2 skeins of silk ($.08).” Ardelia’s young cousin, Walter F. Cushman, required a “silk handkerchief ($.50) and a cravat ($1.50).” Older family acquaintances also made it into her accounts, Capt. George P. Richardson was a regular customer, buying “kid gloves ($.75), 29 yards of carpeting ($21.00), a satin vest ($3.25), 1 yard cambric ($.10) and ½ dozen buttons ($.03)” all in one day. In total Ardelia kept her account book for four months, had eleven customers and over 150 entries with hundreds of line-items. While I have not vetted the prices she ascribed to them, the items themselves are a boon to any researcher interested in knowing what was available to purchase in America at that time.

Almost equally as fascinating to me are the people Ardelia Ripley chose to include in her assignment and how they fit into Duxbury history. For example, friend Joseph E. Simmons, who’s name is one of the most prominent in the accounts, would one day die in the Civil War at the Second Battle of Bull Run (see the Duxbury in the Civil War article). Captains George P. Richardson and Daniel L. Winsor were prominent civic leaders. Walter F. Cushman grew up to marry Ardelia’s daughter, Lucie. In 1860, Ardelia herself would marry the keeper of the Gurnet Light House, George H. Hall, and have six children. Her son, Captain Parker J. Hall, was one of the most colorful people to ever live in Duxbury (more on him in a future post).

[1] The home of Samuel E. and Sarah Ripley was described in a 1925 The House Beautiful article entitled “The Little Gray House with the Pale-Green Door: One of the Aristocrats of the Cape Cod House.” Ardelia inherited this house and passed it on to her youngest daughter, Lura Cushman Hall.