Letter written by Samuel L. Winsor to his brother in 1850 describing the fire at the Weston house. The letter was recently acquired by the Drew Archival Library

Carolyn Ravenscroft, Archivist

Just after midnight on March 29,1850 an Irish servant in the employ of Gerhsom Bradford Weston awoke to the smell of smoke. After giving an alarm, she, along with the large Weston clan, ran from the house in their nightclothes and watched in horror as the quickly moving blaze burned the stately home on Harmony Street (today’s St. George St.). Despite the best efforts of the volunteer bucket brigade, almost nothing could be saved of the contents of the house – portraits, jewelry, furnishings, and even $4,000 in cash were all lost within a few short hours. The total loss reported by Weston’s secretary, William Ellison, was $55,000 ($1.7 million today).

Two letters at the Drew Archival Library recount the fire. One, written by Louisa Bradford Thomas, the Weston’s neighbor at 4 Cedar Street, gives an eye-witness account of the “melancholy spectacle” to her niece, Isabel Kent. The Weston family, turned out of the house without so much as stockings on their feet, made their way to a friend’s house and sent a note to Louisa Thomas for clothing, which she was able to supply. According to Mrs. Thomas, the family lost “the accumulation of thirty years, from all parts of Europe, besides portraits & treasures.” The other letter, only recently acquired by the Drew Archival Library, was written by Samuel L. Winsor to his brother, Capt. Daniel L. Winsor. It gives particulars gleaned from speaking to William Ellison about what transpired on the night of the fire. He records the only items saved from the blaze were “the piano, sofas, front door, 1 carpet and 1 painting.” Both letters refer to the fact that the house was uninsured, but Winsor gives added detail, i.e. “no insurance on the house or on furniture! Never was insured…Boston & Country offices had heretofore refused to insure on account of so many fireplaces.” Perhaps most amazing to Winsor was the loss of “gold watches on the stands – 4 of them in the house.”

Had the fire happened at a different time, perhaps a few years earlier when the great Weston shipbuilding firm begun by Ezra “King Caesar” Weston I in 1764 was still one of the most profitable and recognized in the world, the loss would not have been so catastrophic. But for Gershom Bradford Weston, the eldest son of Duxbury’s second “King Caesar,” Ezra Weston II, the house and its contents now represented almost the entirety of his net-worth. Typical of the later generations of great merchant wealth, G. B. Weston did not produce income, instead he spent it to promote worthy causes, such as abolition and temperance, and to advance his political career. Also perhaps a bit too typically, he did not see the need to curtail his expenditures once the bulk of his inheritance had been reduced to ashes. He moved his family to temporary quarters in Boston and began the rebuilding of his estate – even larger than before. To pay for the new house he borrowed heavily from his younger brother, Alden B. Weston, and allowed him to hold the mortgage.

During the 1850’s and into the 1860’s Gershom Bradford Weston may have felt the pinch of his reduced circumstances, but to the outside world nothing had changed. He continued to be active in local and state politics, and even ran as the Free Soil Party candidate for the Congress in 1852. In 1860 he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln. During the Civil War he tirelessly worked to recruit men from Duxbury to serve in the Union Army and was instrumental in seeing that Duxbury soldiers received the bounties that were due them.

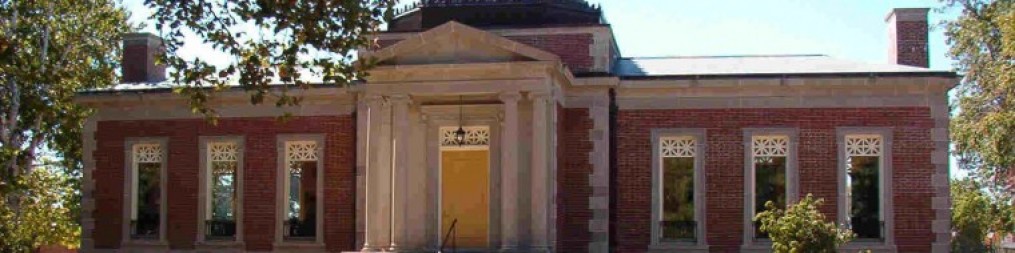

Mansion rebuilt by Gershom Bradford Weston, later owned by the Wright family. It was torn down in the late 1960s

Despite his unflagging political and social career, financial troubles were on the horizon. In October, 1864 Weston mortgaged the entirety of his personal property to his son Alfred for $3,288.50 with the understanding that all property would remain in the hands of Gershom Bradford Weston and he had the right to purchase it back within five years. Included in the inventory are his horses, Charley and Poppit, a variety of carriages and buggies, livestock, and home furnishings. Nothing in the inventory is as elegant as the descriptions of those items lost in the fire 14 years earlier – there is only one gold watch this time. The following month Weston wrote out an inventory of his real estate holdings under the heading “Judgment for the sum of $11,755.54, Executed 30 Nov 1864.” But the biggest financial reversal came in 1867 when, after years of estrangement and litigation, his brother Alden called in the mortgage on the Harmony Street property. Once again Gershom Bradford Weston found himself turned out of his mansion – only this time there was no hope of getting it back.

In what could be considered a cruel twist of fate, Weston rented a house just on the edge of his former estate (21 Pine Hill Ave.). He therefore had a front row seat as he watched the new and fantastically wealthy owners, George and Georgianna Wright, take possession of it. When word reached his Boston friends that the house Weston was renting was to be sold, forcing him to move yet again, they took up a collection and purchased the property – putting the house in his wife’s name to keep it from the creditors. Gershom Bradford Weston died in 1869 at the age of 70. When his brother Alden died in 1880, the original Weston mansion (today known as the King Caesar House), the final vestige of the once great Weston dynasty, was sold and turned into the Powder Point School for Boys.

Sources:

Browne, Patrick T.J. King Caesar of Duxbury: Exploring the World of Ezra Weston, Shipbuilder & Merchant. Duxbury, MA: Duxbury Rural & Historical Society. 2006.

Weston, Edmund Brownell. In Memorium: My Father and My Mother Hon. Gershom Bradford Weston, Deborah Brownell Weston of Duxbury, Massachusetts. Providence, RI. 1916.

Louisa B. Thomas Letter in Bradford Family Collection, DAL.MSS.024, Drew Archival Library

Samuel L. Winsor Letter (1850), DAL.SMS.068, Drew Archival Library

Financial papers, Alden B. Weston Collection, Drew Archival Library, DAL.MSS.056

Date Board House Files, Capt. George Peterson House, 1801, Drew Archival Library