The Drew Archives recently acquired the letter of Sarah F. Sampson to Jacob Smith, Jr. (1836) DAL.SMS.063

Carolyn Ravenscroft, Archivist

At 9pm on the night of September 11, 1836, Sarah F. Sampson sat in her bedroom and wrote one last love letter to her cousin Jacob Smith, Jr. It was Jacob’s 25th birthday but she did not mention the occasion in her letter, perhaps she had forgotten. What she did mention, repeatedly, was her devotion to him. This could not have been an easy thing to write, as Jacob was due to marry Persis “Ann” Weston, another cousin, in less than a month. At no point did Sarah implore Jacob not to marry, she even wished him well, but it is clear she would rather he had chosen her.

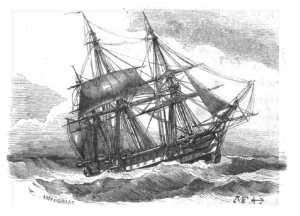

Sarah Freeman Sampson was born in Duxbury on March 1, 1813 in the cape-style home her father, Martin Sampson, had built in 1807 (today’s 57 South Station Ave.). Sarah’s mother died within months of her birth, leaving her father to care for her as well as her two siblings, ages 3 and 5. Not surprisingly, Martin chose to remarry rather quickly, and it was through Martin Sampson’s second wife, Sarah Smith, that Sarah F. would become related to the recipient of her letter. Jacob Smith, Jr. was Sarah Smith’s nephew. Not that their paths wouldn’t have crossed without this connection – Sarah’s house was only a stone’s throw to Jacob’s, he living at what is today 251 Harrison Street. But, the inevitable family gatherings must have made the two much more aware of each other. And young Jacob Smith was certainly someone to notice. By 1836 he was already first mate on his father’s brig, Globe. He had gone to sea when he was only eight, celebrating his ninth birthday in Malaga, Spain. According to one source, at age eleven he had been paraded in front of Russian nobility in St. Petersburg as the first American child they had ever seen. While many Duxbury sailors could tell tales of far away places to impress the ladies, Jacob had the advantage of being young, wealthy and having great prospects. His father, Capt. Jacob Smith, Sr., was an important member of the town who not only owned a number of Duxbury properties, but also a large farm in Marshfield. Is it any wonder that Sarah F.Sampson was smitten?

How Jacob received his cousin’s letter, or whether he returned her sentiments, is impossible to know. Sarah’s letter does indicate she had received an equally private one from him so there may have been complicated feelings on both sides. Regardless, he went ahead with his wedding to Persis Ann Weston in October, 1836. Persis, or Ann, as she was called, was the niece of his step-mother (like Sarah Sampson, Jacob had lost his own mother when he was very young). Married life did not keep him at home, at least not initially. As the captain of his own vessel, Jacob traveled around Cape Horn and up the western seaboard in 1837, trading with the natives for sable furs which he sold back in New England. In 1838 he was in London to see the coronation of Queen Victoria. At the age of thirty, having been aboard a ship more often than not, he retired from the sea and moved to Westford, MA. There he owned an historic tavern, became a gentleman farmer and was active in local politics – he served as a Selectman during all four years of the Civil War. He died in 1898, the oldest man in Westford at the time, leaving behind his wife, Ann, and two daughters – Miss Clara A. Smith and Mrs. Louisa D. Young. A son, Henry, had died in a tragic rail road accident at the age of 21 in 1863.

Lest you feel too badly for Sarah F. Sampson, let me assure you she married well and had a happy life (or as happy as we can surmise from the scant information left to us). In 1840 her heart was mended enough to accept the proposal of a very successful dry goods merchant from Medford named Jonas Coburn. Together they had five children: Sarah Louise (b. 1841), Charles F. (b. 1843), George M. (b. 1846), Frank (b. 1853) and William (b. 1854). All lived to adulthood but William who died at age 4. The Coburns were very active in civic affairs and were substantial members of the community. As a memorial to their parents, the children of Jonas and Sarah had a stained glass window installed in the First Parish Church in Medford that can still be seen today.

During the summer months Sarah would bring her family to Duxbury and stay with her unmarried sister, Hannah, in her childhood home. After Hannah Sampson’s death in 1882, the house was left to Sarah and her children who retained the property as a summer residence into the 20th century. Sarah Freeman Sampson Coburn died in Medford, MA in 1890, at age 77.

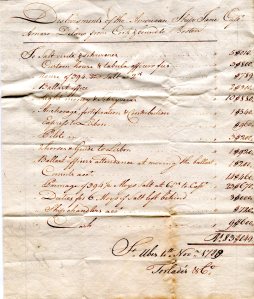

The following is a transcription of the letter Sarah penned late at night to “the one person I really did love.”

Jacob Smith, Jr. Chief Mate of the Brig Globe, Boston

Duxbury Sept. 11, 1836

Coz Jacob,

I received your letter last Saturday & was not a little surprised at its contents. You say that you heard I was keeping school & Mr. Lovell often called & stopped after school. What do you mean? I entreat of you Jacob to answer this the moment you have read it & tell me where you got your information. I now call upon you as a friend to listen impartially to a fair statement of facts. In the first place I have neither seen or heard from a Lovell since last winter, & in the second place, Mr. Lovell never was the chosen object of my affection, I liked him as a friend but I did not love him as – I can think it but I can’t say it. No Jacob there never was but one person that I thought I really did love. You undoubtedly know who I have reference too. I have loved, shall ever love him. But that love will never be returned, another will have that privilege (in other words does have) it is a privilege indeed!!! Let him go, but he carries with him the most devoted affections of one who never knew love till she saw him & who will never know – I will stop where I am for I have already said too much. But you know me too well I shall therefore entrust this to your honour, as I have done heretofore. As it was your request I have kept your letter private & I now ask the same of you. Don’t you show it at your peril for I have written it from the impulse of the moment. A few more brief sentences & I will close. Mr. Stetson & the will be Mrs. Stetson returned last night. I have not yet seen Martha, but I saw Mr. Stetson to day & dined with him. He says you are the some old six pence or I believe it is now “2 & 6 pence.” By the way I saw Sarah Loring last Sunday, but did not speak with her. Martha R. has just gone from here in all her beauty. She wished to be remembered to you. She is a friend if ever there was one. I would not part with her for all the girls there are in Duxbury. I forgot to mention that I have a letter from cousin N. F. Frothingham to day, he writes he is coming down in a few days. I shall be happy to see him & I think I should like to see you a few moments (or so) as Aunt Shere says & taken a dish of sociability. By the way have you forgotten the day that G. M. Richardson & myself spent at your house? I have not. It is imprinted on my [heart] in indelible

Portion of Sarah F. Sampson Letter

characters. Hark!! The clock is striking 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Oh Dear me I must draw this protracted scrawl to a close. When I first began it was past nine & I thought I would just write a few lines & ask for an explanation of your letter, which I beg you will favour me with, on the reception of this. Jacob you must excuse the writing, [editing] & orthography of this letter for I am positively half asleep. Pardon me for not previously mentioning the name of Ann. Heaven smile on you both & bless you, may your cup of happiness be ever full even to overflowing. May no cloud interrupt the sunshine of your days, & when at last you are called to part from her here, may you be reunited in that world “where the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest” is the sincerest wish of

Your aff cousin

S. F. Sampson

In two minutes more I am tucked up in bed fast asleep

N.B. & P.S.

I am so sleepy that I cannot possibly read this over. If I have written anything improper I beg of you to excuse it & take it from whence it came.

Good night

Sarah

Answer this full of news

Love to all

Note: Mr. Lovell is a mystery at this time but some of the other names a known. Mr. and Mrs. Stetson are Jacob Smith’s brother-in-law, Samuel Stetson, and sister, Martha. Samuel Stetson was a lawyer and the couple lived on Tremont Street.

G. M. Richardson was most likely part of the Richardson family that owned a large estate adjacent to Sarah F. Sampson’s house. The estate was once owned by George Partridge, one of Duxbury’s most prominent citizens and inherited by George P. Richardson. Martha R may be Martha Richardson (b. 1815).

N.F. Frothingham is Nathaniel F. Frothingham of Charlestown, MA whose mother was Joanna Sampson of Duxbury. He married Margaret T. Smith, the daughter of Capt. Benjamin Smith and cousin to both Jacob Smith, Jr and Sarah F. Sampson. It is interesting to note that Frothingham married Margaret on Sept. 30, 1836, just 19 days after this letter was written.

Sources:

Drew Archival Library, House Date board Files – Martin Sampson House and Daniel Bradford House

Drew Archival Library, Capt. Jacob Smith Collection

Find A Grave, Jacob Smith, Jr, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=124241863

Unitarian Universalist Church of Medford, http://www.uumedford.org/history.html

Leading manufacturers and merchants of eastern Massachusetts: historical and descriptive review of the industrial enterprises of Bristol, Plymouth, Norfolk, and Middlesex Counties (Google eBook)

![Delano Triplets, c. 1870 Photographer: M. Chandler [Marshfield, MA]](https://drewarchives.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/delano-triplets002.jpg?w=300&h=191)