The Duxbury Rural & Historical Society recently acquired this photograph of sculptor John Horrigan with Myles Standish’s head, 1930.

Carolyn Ravenscroft, Archivist

Myles Standish was known to have a hot temper but it was not until 1922[1] that he truly lost his head. Shortly after noon on a sultry August day an electrical storm caused lightning to strike the 116-foot monument dedicated to the former military leader of the Pilgrims. The bolt from the sky caused Myles’ head and arm to topple to the ground.

There was no great push to replace his missing granite anatomy so Myles stood headless over Duxbury for four long years. In 1926, a new head was created by Boston sculptor John Horrigan[2]. Unfortunately the old lightening damaged legs could not support their new addition so back to the quarry it went, along with an order for stronger lower limbs.[3] Finally, in 1930, an almost completely remade Myles Standish was placed back atop his perch (his outstretched arm and possibly torso are the only remaining parts of the original statue).

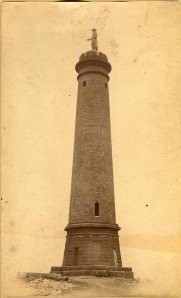

While the damage to its statue was catastrophic, the beheading of Myles Standish was only one in a series of misfortunes suffered by the Monument – and some would say it continues to suffer. The Monument was conceived not by a Duxbury resident but rather by J. Henry Stickney of Baltimore, an admirer of Capt. Standish. The land atop Captain’s Hill, formerly owned by Standish, was deemed the most appropriate spot to place a memorial. Architect Alden Frink’s design called for a 100′ monument topped with a 14′ statue (with two feet between the parapet and the statue, making it 116′ total). Garnering support and enough money to begin the project, the cornerstone was laid on October 7, 1872, with much fanfare and even Masonic ceremonies, in front of 10,000 onlookers. But, after an expenditure of $27,000 the monument was still only 72 feet high. Interest and money waned and it stood half complete until a second wave of donors saw the monument finished in 1898. When you look at the two shades of granite, you can tell exactly where construction originally halted.

By 1920 the Monument and statue were in disrepair. Dr. Horton, the President of the Standish Monument Association, sought $10,000 from the State for repairs and landscaping. According to Thomas Weston’s autobiography, the State could offer no assistance unless it acquired the monument. After persuading the Association deed the land over, a bill was signed by Gov. Calvin Coolidge, allowing for Massachusetts to become its owner and caretaker. [4] Thus, when Myles lost his head, the State got the bill.

Today the State still gets the bill, but with so many other pressing responsibilities, the upkeep and opening of the Myles Standish Monument has become a bit overlooked. Despite this, however, Myles, with his reconstructed head and body, still stands tall.

[1] “Bolt Beheads Myles Standish Statue on Duxbury Shore,” Boston Sunday Globe, August 27, 1922. This date has been misreported over the years as 1903, 1920 and 1924. However the actual storm hit on August 26, 1922, two years after the State of Massachusetts took control of the monument from the town.

[2] S. J. Kelly of Boston designed the original statue. It was sculpted by Stephano Brignoli and Luigi Limonetta of Bayeno, Italy using granite from Maine. The Monument was designed by architect Alden Frink.

[3] The lower legs were left at Horrigan Granite Co. in Quincy and later ended up in Halifax.

[4] Excerpt from the autobiography of Thomas Weston in Don H. Ross, “The Mystery of Captain Myles Standish’s Legs”, 2001, p. 12.